How to Have Opinions About Everything (even things you shouldn't have an opinion on)

TikTok comments might be ruining my life

Last night on the phone, Will said “I really want to see Anora”. The movie had just won five Oscars, including Best Actress and Best Picture.

Without hesitation and for no apparent reason, I responded with: “Yeah…but I heard it was pretty male-gaze-y. I saw this one TikTok where one of the extras was like it opens a door for sex worker representation in media, but I’m excited for when we get to tell our own stories rather than have them depicted through a man. And everyone’s mad that Demi Moore didn’t win for The Substance.”

In case it isn’t clear, I’ve never seen Anora. I’ve never seen The Substance either.

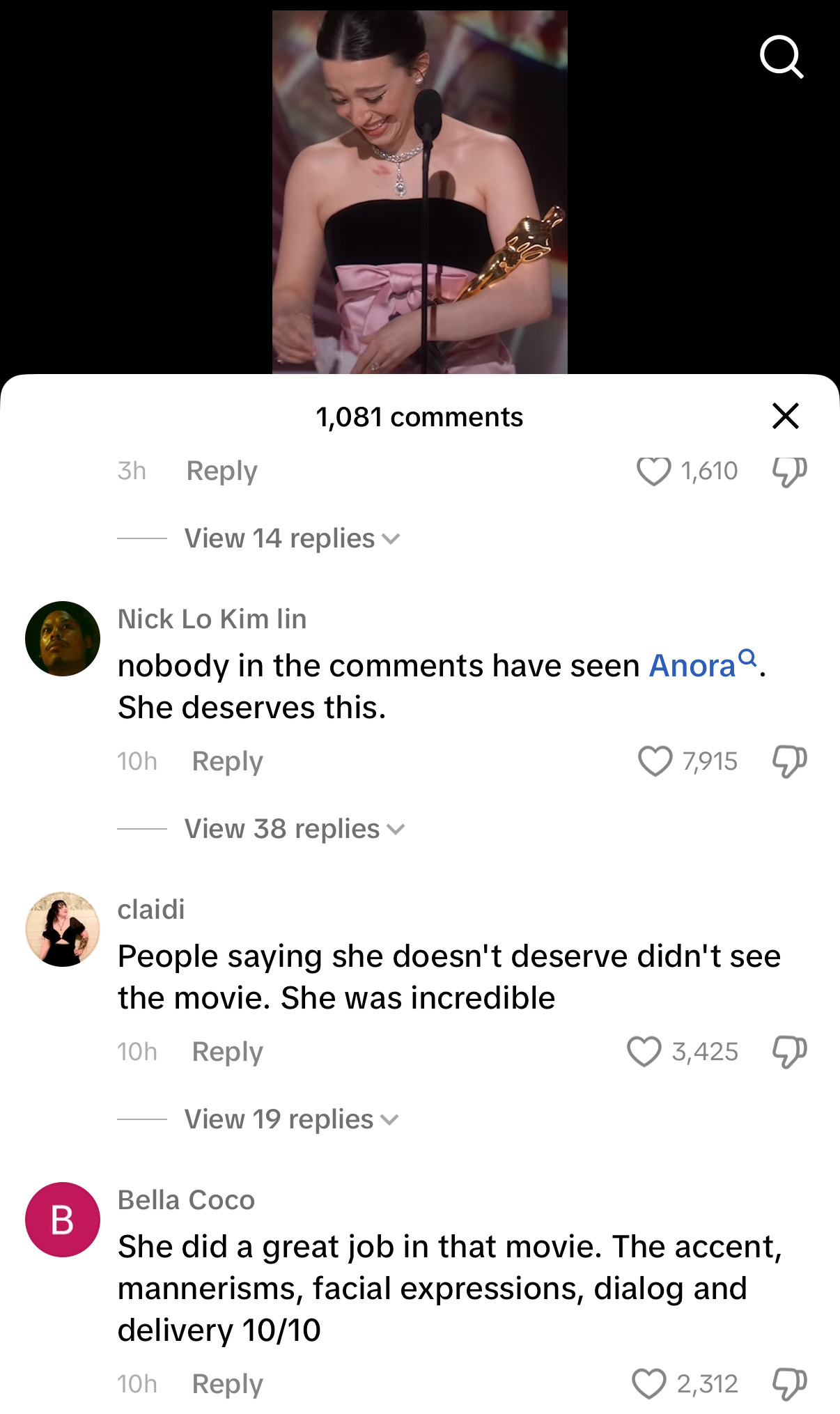

Then, during my morning scroll, I sent the following TikTok to Will, as if to support my point that Anora’s success might be undeserved:

But Will has always been too smart for my antics. He texted me back: “Do you think Poor Things and Emma Stone was different?”

Rats! He got me there. I really liked Poor Things when I saw it last year. I had nothing critical to say when Emma Stone won Best Actress for Bella Baxter. I replied with an audio message, the tone of which became increasingly distressed:

“No! I don’t think Poor Things and Emma Stone was different. I actually think…I liked the movie when it came out, but honestly, in the year and a half since…well—the truth is, Will, I just don’t think I have opinions of my own! I think…the truth is I’ve just, like, read more criticism about Poor Things and so I’ve adjusted my thoughts accordingly. But, no—I think it’s exactly the same. I’m just a sheeple. I’m just reflecting the literal TikTok comments and Substack essays that I’ve read and I haven’t even seen Anora…like obviously I’m just a faker…I’m just sitting in my room regurgitating the stupid little TikTok comments I’ve read. So actually, I feel really bad about myself, and…the end.”

A few minutes later, I sent him this screenshot:

—

I’m a firm believer in trying on opinions to develop your critical voice. I taught a high school English class last year, and by far the hardest part of leading seminars was coaxing a room of nervous kids to say something wacky about whatever we were reading. It was always easy for them to say “x was good” or “x character is mean,” but the fun, dynamic work of media analysis lies on the border between observation and experimentation. What’s your least favorite word in that sentence and why! I would exclaim at my class. What do you think is the weirdest thing that happened on this page?!

When you let yourself approach criticism as an act of play, you discover the opportunity to uncover your most clarified, creative opinions. Yes, learn how to write an essay. Definitely learn how to structure an argument. But I think the most important part of consuming media is allowing yourself to actively engage with it—to experience your artifacts as live objects, where the things that you notice and the patterns that you find offer personal texture to your claims.

Books, movies, TV shows, paintings…they are all themselves creative products and objects of a creative process. The fun of criticism, I think, lies in one’s practice of approaching any work as a creative process unto itself—in treating viewership (or readership) as an opportunity to test ideas and refine the art of your own perspective. And you don’t have to universally like something for this model to apply. I hated Kaveh Akbar’s Martyr!, but I loved the process of uncovering the words that conveyed why and how the book made me feel, “I don’t like this”.

This critical approach based in play necessarily emerges from a process of “seeing what sticks”. Sometimes you’ll write an entire essay about your favorite word from one scene of The Tempest, and that essay won’t be very good. Sometimes you’ll choose to focus on the music of a film and realize in the process that you don’t have the language to discuss film music, and that’s okay—good, even. Flops illuminate where your current weak points lie; they show you where to improve. And you’ll often be surprised by what does work. Nothing hones our abilities to articulate ideas like attempting to articulate ideas, and sometimes one of your ninth graders will write about Mollie as an example of coquette-core femininity in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, and that essay will be a deeply creative success.

We need to have opinions. On everything. We need to watch how other people have opinions and learn from what we like and dislike about their arguments. No one becomes a critical thinker without training their thinking through trial, error, and enthusiasm. There is good work to be had in having something to say, especially when you don’t know how to say it. We only get better by trying.

—

But it is hard, I think, to maintain that position when your source material becomes the opinions of others.

I attended a Super Bowl party a few weeks ago, and at the end of Kendrick Lamar’s Halftime Show, there was an acknowledgment in the room that it would be great when the internet “explained” the performance’s hidden meanings to us. What does it mean that we sat there, the group of us, and decided that we would be better off going back to our own bedrooms that evening, opening up our own apps with their own algorithms, and determining how to feel about the Halftime Show based on voices from the cyberspace? While we were watching the Halftime Show.

How can we build community with others through sharing our thoughts when there’s always millions of internet strangers to do the work for us? What voices begin to define us?

This sort of thing happens to me all the time. Sometimes I want to know what Reddit thinks of the world in Flow. Sometimes I hear about news exclusively through the internet jokes that get made in reaction to it. How do we learn from the commentary of others while giving ourselves permission to test our own perspectives too?

With Anora, I had things to say—too much to say—despite never having seen the film. I wasn’t just “taking inspiration” from criticism that came before me, I was carving a baseless stance for myself on the weak foundation of other people’s thoughts. Short-form plays a huge role for me here; it is so damning to see one negative TikTok amidst the constant deluge of content. Full-length feature films have the potential to be leveled by one scathing line from one TikTok by one random creator some unknown number of weeks ago.

Do you know what I was doing in the countless hours over the past few months when I could’ve watched Anora? Probably watching TikToks. Not only did I still have thoughts about the film, but my opinions came from mere seconds of seeing comments and hearing red-carpet soundbites.

As reactionary content continues swallowing our attention to become the primary media we consume, what’s left of all the other stuff? It’s remarkably easy to understand the cultural conversation of so much media these days, without ever engaging with the conversation’s source material. The heinous clips and ensuing criticisms of Emilia Pérez, for example, were surely enough for tons of people to avoid watching the movie altogether, despite being familiar with its most notable songs. The It Ends With Us trainwreck has countless controversy breakdowns across journalism and social media, and nobody’s requiring you to see the movie (or read the book) to get invested in its surrounding gossip. In many cases, it is the total norm to rely on what other people are saying to take a side in social opinion. In many cases, it is extremely fun (and always easiest) to be swept up in the fervor of how your corner of the internet already feels about everything.

—

Realistically, I can’t offer a full-scale rejection of TikTok. I obviously enjoy it, and I think there’s real humor and interest to be had in the platform. I would be lying if my conclusion was just delete TikTok. It’s probably a good conclusion—the kids and their damn phones and all. But it just won’t happen for me.

Maybe the solution is the completely easy, totally obvious one: watch the movie before you talk about it. When Will says “I really want to see Anora,” you respond with “Yeah, cool, I haven’t seen it yet”.

But nobody’s an island when it comes to this stuff. In the same way that social media pulls our interest away from books, movies, and television, capitalism forces urgency upon us to spend our limited leisure time consuming the right media. It’s not good enough anymore to be an exciting movie, because we have excitement on demand on our phones at every second of every day. The movie that pushes us to click rent now or drives us to the movie theater has to have buzz and acclaim, big stars or strange PR. If Anora hadn’t been nominated, would Will have wanted to see it? Probably not. He wanted to see it because it was nominated, and he really wanted to see it because it won. In this framing, my quick resistance to the film isn’t way more arbitrary than his interest in it: we are both operating based on systems that have something to gain by getting us to trust their judgement.

And social judgement plays a huge role. When consuming the right media, there’s a consideration of what reflects best on us. If we’re all watching TikTok all the time every day, I can’t judge you for your algorithm and you can’t judge me for mine, because we don’t know what each other’s internet worlds look like. If I go out and watch Anora or Flow or Wicked, that might mean something to you. Maybe I care too much about independent films (therefore I’m elitist and pretentious) or maybe I only watch blockbusters (making me uncultured and undiscerning). As long as our claim for or against something aligns with politically defensible standards, our groundless reasons to watch (or avoid) that thing become a bit more grounded. My concerns about Anora? Vaguely: sex sells, patriarchy bad, something something male gaze. And now I’m not just someone with opinions, I’m someone taking a stand in the negative space of my inaction.

But suffice it to say that “sex sells” and “patriarchy bad” demonstrate the TikTokification of my sociopolitical opinions too. I’m not any more of a strong advocate for women by avoiding Anora than I would be by watching it. Even the suggestion that I might have robust enough feminist ideals to feel a certain way about a movie that I haven’t seen is performative, and it has dangerous implications. As “the revolution” becomes cute-winter-boots-ified and entire movies become one holding-space meme after the next, what lies below any of it? What convictions do we hold by ourselves, when the memes finally run dry and we have to think and feel?

—

Social media, comments, clickbait—all of this content excels at trafficking loud opinions in tiny instances. Consuming so much of what I’m calling reactionary media enables me to mirror that standard of big-thought-no-context or negative-take-no-substance with frighteningly everything. We live in a world of quick soundbites and “What’s your take?"s, so we have to be ready at any moment to cobble together enough vitriolic TikTok comments to take down every movie we’ve never seen. Because God forbid we spent all our time on our phones instead. There are ways to make every choice seem intentional, every decision righteous, if only someone on Reddit said it first.

It is so hard to deny yourself the ease of aligning with your algorithm’s cacophony of sirenic voices, and every stakeholder on the other side of your screen profits off of your inability to pull away and form an opinion for yourself. I’m not saying you have to watch Anora (though I will), and I’m not saying that you have to delete TikTok (because I won’t). You can even follow me on TikTok, where I do Words About Things by Mr. Sara in a short-form-video way!

But returning to my English class, returning to my thoughts on criticism and play, I think we have to spend as much time producing ideas as we do consuming them. We may never be able to cleanly extricate The Powers That Be (our phones, the Academy, capitalism) from our critical minds, but there is immense value in remembering that our critical voices can still be honed within The Powers That Be. Share your own thoughts before turning to your algorithm, absorb the drama and then test what you’ve heard about a movie against how that movie makes you feel. Take inspiration from what other people notice and see which frameworks fit best with the content that you care about most.

There is so much to be gained from trying on ideas, and it’s critical to remember that our algorithms aren’t motivated by our creativity and joy—they’re motivated by our attention. We need to watch and listen and feel, and we need to talk to people we know about the things we’re thinking about before letting people we don’t know force-feed us opinions about the things we’re not thinking about. Who cares! Who cares about the stuff they’re telling you to care about! What do you care about? What do you think is the weirdest thing that happened on this page?!

Watch and read whatever you want, but remember to sometimes watch and read what you don’t gravitate towards, too. Don’t be afraid to listen to the voices on your phone, but always remember to give yourself more credit than the ether. And when you do listen to the internet voices, pay attention to the strength of their arguments and not just the content of their claims. Spend half your time watching a movie trying to get the hype and the other half of your time trying to unpack the criticisms. See what sticks, don’t be afraid to change your mind, and if, at the end of the day, you still have something negative to say, say it with the confidence of your conviction, because we only get better by trying.

yes yes and yes to this piece!! makes me think of that quote from norwegian wood: “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

Maybe it is different from poor things