Whenever you read Lorde commentary, the story always begins with profound personal resonance.

I grew up with her, her music ushers in new phases of my life, she makes me feel understood and opens a portal to the next version of myself.

This deep relatability isn’t a coincidence; Lorde’s most popular albums (Pure Heroine and Melodrama) lend themselves to an intense listener identification experience from top to bottom. When she sang I’m 19 and I’m on fire, an entire generation of young adults felt like she had distilled and released something burning in them too.

The problem (or brilliance) of Lorde is that her two most recent albums (Solar Power and Virgin) function as musical diaries. Lorde’s use of “I” has sharpened over time, all but erasing easy identification with the narrator of her songs.

Lyrically, I don’t love Virgin. As I’ve already written, I think it’s kind of goofy. But the foreignness I feel toward Lorde’s hyper-personal lyrics signals that she has accomplished something: Lorde has created a work which makes me reconsider my relationship to its author. Virgin, whether you like it or not, is Lorde’s most successful project of autofiction to date.

—

Pure Heroine and Melodrama belong to the listener as much as they belong to Lorde as an individual.

In her debut album, Lorde is at her most diffuse. From the album’s universal themes (teen angst, young ambition) to Lorde’s constant use of “we” (we’re never done with killing time, we’ll never be royals, we’re dancing in a world alone), Lorde functions as a convenient narrator for the music more than a particular identity.

Pure Heroine’s cover is bold and simple. The three gray words on black text reflect the strong potential for listener identification with Lorde’s use of “I” in Pure Heroine. She does not put her face on the album, does not force the stark specifics of her life onto yours. As much as pop music can, Pure Heroine functions on behalf of collective feeling.

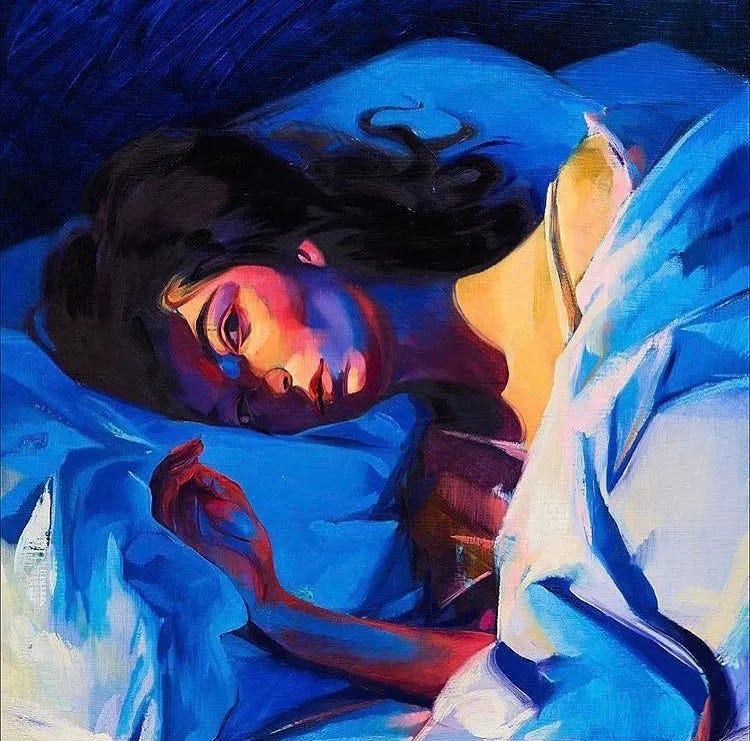

Melodrama stays within this vein. On her sophomore album, Lorde draws more from her own life experiences, but lyrical imagery works to generalize the album’s themes of love, loss, and coming-of-age. Waiting for the green light, being hung in the Louvre, feeling like a liability—Lorde’s use of vivid figurative language enables the casual listener to identify with the album’s narrator through Melodrama’s highest highs and lowest lows.

The audience is referenced as an object in Melodrama, like at the end of “Liability” (You’re all gonna watch me disappear into the sun) and through most of “Perfect Places” (Are you lost enough?). There is a creeping notion, then, that Lorde is gaining a sense of separation between herself and her audience, but lyrics like I do my makeup in somebody else’s car aren’t so personal as to distance the listener away from Lorde’s use of first-person. For all intents and purposes, the listener is invited to Lorde’s party.

The album cover depicts this shift perfectly: Lorde’s face is on the cover, but it’s an oversaturated dramatization of her being. The moody colors blur out stark reality, much like the heightened emotions of Melodrama’s lyrics deny over-specification to Lorde as an individual. She’s looking right at us in the vulnerability of her bedroom, but just like in her music, Lorde is more evocative than she is photorealistic.

—

Solar Power, of course, is where things really change. A softened sound, an aimless guitar…stoned reverie skipping around climate anxiety, grief, and the false confidence of one’s early twenties. Lorde opens the album with lyrics cut from her own singular life (teen millionaire having nightmares from the camera flash…won’t take the call if it’s the label or the radio). What, then, with the listener?

In baring her fame, Lorde toys with her audience, from I’m like a prettier Jesus to now if you’re looking for a saviour, well, that’s not me. The audience is pushed away from identifying with Lorde’s use of “I” because it’s clearer than ever that Lorde’s first-person belongs to Lorde alone. Again, the album cover symbolizes this change.

Lorde’s position as the narrator is as clear as a photo, and the audience is positioned from below while their pop star sings of life from above.

Solar Power can be understood as a collection of messages from Lorde to various objects. Sometimes she sings to the listener, sometimes she sings to her past self, sometimes she sings to the memory of her dog, and sometimes she sings to her lover. The recipient changes, but Lorde-as-subject is more restricted than ever. It is an album that is for the listeners but never of the listeners.

—

On Virgin, Lorde leaves the listener out altogether.

Just like with Solar Power, Lorde is the unquestioned narrator of every song on the album. But on Virgin, Lorde loses all cheeky pretense of playing with the distance between her and her audience. She ends the opening track with til I’m just a voice living in your head…I’ve sent you a postcard from the edge, and then the listener isn’t acknowledged for the rest of the record.

Lorde sings to lovers and exes, she sings to her mom and to herself, but she never sings to the listener. All the audience gets is the album—a postcard from the edge, to treasure or discard.

The cover shows an X-ray of Lorde’s pelvis, depicting Lorde in medically-precise, brutal honesty. Virgin is a project of autofiction, through and through. During press, she referred to the work as THE SOUND OF MY REBIRTH, and where fans saw “rebirth” and thought Pure Heroine, they should have seen “my” and thought Solar Power.

Because while there are wide moments of relatability (relationships, eating disorders, womanhood), the specificity of Lorde’s lyricism forces the listener to principally consider rather than identify with. This is evident in a song like “Favourite Daughter,” where the theme is general and relatable (hard-working child constantly seeking the approval of their mother), but the lyrics are particular (You had a brother, I look like him / you told us as kids / “he died of a broken heart”).

In order for an album like this to sink its claws into the listener, that listener either needs to love the sound more than they care about relating to the lyrics, or they need to respect or identify with Lorde’s hyper-specific lyrics so much that her diary remains captivating. Above all, Virgin is by and for Lorde.

—

It’s still very early, but I’m less interested in listening to Virgin at this point than I have been with any of Lorde’s previous albums.

As a longtime fan, I’m bummed. But maybe my disappointment is proof that Lorde perfectly accomplished what she set out to do: be herself, down to the bones, and let those who appreciate her stripped-back frankness celebrate the work for what it is.

Because the early Virgin reviews I’ve read are polarized in the exact same way that contemporary autofiction can be polarizing—either you think the writer is a self-important asshole who lacks relatability and gets too navel-gazey in the cringiest ways, or you think the narrator’s self-exposure emphasizes the texture of your own life more clearly. It’s no surprise that Lorde has publicly referenced and praised Sheila Heti, Rachel Cusk, and Ben Lerner in the making of Virgin.

But those authors work in a different medium and come from a different stratosphere than Lorde. She is, for better or for worse, a mainstream pop star who became well-loved with highly relatable, upbeat pop anthems like “Green Light,” and now she’s crystallizing her own self-mythology, anguish, and ecstasy into thin, three-minute electronic-pop tracks.

I think Virgin is a unique piece of musical autofiction that distills the raw life of a very out-of-touch, self-proclaimed spiritual technologist and mystic. But is it a great pop album in the sense that I’ll ever play it at a party with my friends? In the sense that it will serve as the soundtrack for the next era of my life? The answer might be no.

—

UGH, Lorde is a tough one. I identified so strongly with her early work, and she’s always seemed so cool in her press. My support has been a little parasocial, but she’s been sold as something of an intellectual’s pop star—writing poetic emails to her fans, seeming articulate and authentic in interviews.

But Lorde increasingly wants to remind me that I’m listening to the sounds of her life, and her life has increasingly become less relatable to me. The goofy lyrics and the electronic beep-boops are too sparse to carry the weight of my expectations for Lorde, and I’m left feeling underwhelmed by Virgin every time I listen to it.

I don’t think Lorde has gotten worse, exactly—I think her vision is more clarified than it’s ever been. The strength of the album and my sadness as a Lorde fan are rooted in the same truth: I’ve finally realized that I’m not as much like her as I’ve always projected, and that’s okay with me. All of our heroes fading, you know?

Ok OBVIOUSLY not the point but it’s interesting that the South Park Lorde parody from 2014 sings “I am Lorde, I am Lorde.” They thought it was unrelatable autofiction then!

I'm not sure a Lorde album will ever top 'Melodrama' for me, but I actually think 'Virgin' is a brilliant album! While 'Melodrama' perfectly soundtracked my messy later teen and early adulthood years where I craved music that was relatable and spoke to my life at the time, I feel that nearly a decade later I'm able to enjoy music that doesn't just speak to my own experiences. I enjoy imagining myself in her shoes as I listen to this one. There are still moments that are relatable and I feel the kinds of feelings that 'Melodrama' and 'Pure Heroine' provoked in me, but I love 'Virgin' partly because it isn't entirely relatable.